Raphael (Raffaello Sanzio or Santi, 1483-1520), one of the key figures of the Italian Renaissance, is reborn within the National Gallery’s walls. “This exhibition [is] the first outside of Italy to encompass all aspects of Raphael’s artistic activity across his career”, the Gallery states. The National Gallery, partnered with Credit Suisse, encapsulates not only Raphael’s skills as a draughtsman and painter of oil and fresco for which he is famed, but also his accomplishments as an early archaeologist supervising excavations of ancient Rome, his architecture, and his designs for prints, tapestries, decorative art- the list continues.

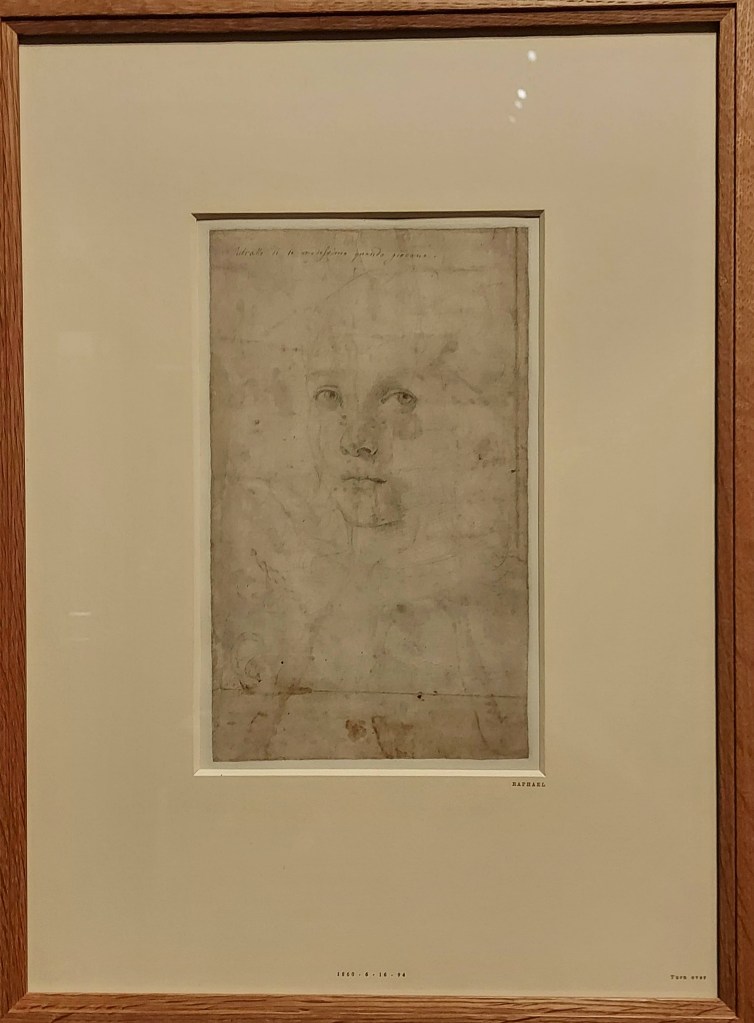

Raphael was the son of Giovanni Santi (c.1440/5-1494), a court painter to the prominent Dukes of Urbino in eastern Italy. Raphael had a brief career, dying suddenly at 37, yet within those years he excelled across a wide range of media, examples of which have been masterfully curated within this exhibition, charting his “phenomenal success and extraordinary energy”. Creations by the master’s hand have been honoured within 7 high-ceiling rooms of the main gallery, spanning his ‘Early Works’, which opens with Head of a Boy (Self Portrait?), c.1498 and highlights the early talent of Raphael around 15-16 years old, through to ‘Friends & Patrons’, which solidifies the legacy of a man determined to inspire human connection through his artwork.

As Raphael develops his skill, repertoire and clients, his workshop grows simultaneously, and he selected his best students to aid him with the production of large works, a delegation technique which enabled him to create the sheer volume of work that he has amassed in his brief career, while improving the work of other aspiring artists.

Exhibition Highlights

One feature of Raphael’s artworks that held my gaze is his connection. Whether its the subject’s eyes fixed on the audience, staring out from the frames, or the body language between multiple figures within a composition- Raphael not only painted a representation of life, but captured a moment of it. With carefully rendered touches of hands, angles of the body, light within the eyes, Raphael longed for the connections he lost himself- losing his mother at age 8, and his father at 11. He did create those relationships, with friends, collectors, artists alike. He develops those connections with us, as we stand among the sumptuously robed figures of his larger works, and side-by-side with our fellow exhibition-goer. Raphael, through the timeless integrity of his work, continues to forge these connections today.

I’ve placed these portraits together above to highlight how Raphael’s confidence grew along with his skill. We compare one (likely) self portrait drawn around age 16, with the later oil on wood by a more mature Raphael. From the soft medium of chalk to the vibrant and heavy oil rendered on solid wood, Raphael’s artistic decisions are bolder, notable in the contrast from the light background to his dark robes and cap which dominate the foreground and our focus. The soft shadow to the right of the wood panel exemplify how Raphael’s dexterity and his blending of contrasting oil tones has improved from earlier works, and this visible improvement continues throughout the exhibition.

The best advice I’ve ever been given was “Paint what you see, not what you think you see”

Indeed, Raphael said himself that “when one paints, one does not think”: the intention is to shed your preconceptions and observe the shapes and forms that fill your vision.

Its encouraging for an artist like myself, to look back on drawings from when I was younger, looking ahead to what I’ve created since, that when skill is driven forwards with a hunger for excellence, you will improve. I can imagine Raphael’s sigh of accomplishment, stepping back from his self portrait, and I hope he thought “finally, the painting looks like me!” (or rather “Finalmente, il dipinto mi assomiglia!”, as he is Italian). Self portraits can often be the hardest to master, you’d think we’d know our own faces enough, and yet that is our downfall. If you think you know what something looks like, you forget to check your reference. You take for granted the intricacies of the human face.

Raphael’s objective eye for details compounded the realism within his portraits and figurative pieces.

Above left: Altoviti (1491–1557), a Florentine banker living in Rome was a close friend of the Raphael’s. He was a dedicated patron and collector of works of art throughout his life. The Venetian practice of artists was to pose the sitter as though they had suddenly turned to meet our eyes, which Raphael adopts here, creating that feeling of immediate connection I referred to earlier. The light shining across the canvas, originating from the left and casting a shadow to the right, allows Raphael to display his mastery of proportion at complex angles. Raphael surrounds the figure with a vivid green backdrop, using the same colour within the eyes and the sitter’s ring, to further emphasise the subjects piercing gaze upon the viewer, and the high regard in which Raphael held his friend.

To the right: A tapestry from the Workshop of Pieter van Aelst (1490-1533), from a cartoon by Tommaso Vincidor (1494-1536) after design by Raphael, God the Father accompanied by Symbols of the Evangelists, c.1511, made in Brussels wool, silk and gilt-metal-wrapped thread, and on loan from Museo Nacional de Artes Decorativas, Madrid. The tapestry is directly based on the oil painting displayed next to it within the gallery, designed to form the canopy of “a magnificent bed for the room in which the pope was robed prior to ceremonies in the Sistine Chapel”, as the Exhibition literature states. The movement of the robes which surround God and the angels translates seamlessly into tapestry. Raphael was in high demand to create religious frescoes and portraits, notably for both Pope Julius II and Leo X; religion provided a steady income but also endless inspiration for the artist.

The exhibition highlights Raphael’s ability to animate his subjects like Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519), and adapt to the “dynamic expressiveness” of Michelangelo (1475-1564). Sketches within the exhibition show Raphael’s study of these masters of the Italian Renaissance, but the chronology of his work sees Raphael earn the title of Master in his own right, adapting techniques he values from others, and making the medium of oil painting his own. Above, we see the complexity of interaction between the figures of the mother and son, further attesting to his ability to create and immortalise moments of human connection. Raphael created many variations of the Virgin and Child (also described as Madonnas) over his career. The Virgin and Child was first examined by Dr Nicholas Penny, with the findings published in the Burlington Magazine. Leading experts across Europe and America examined the painting and concluded that it is indeed by Raphael.

On the right is detail from the full piece, highlighting the tenderness of touch, soft folds of fabric and skin, the passing of the pink carnation flowers between carefully rendered fingers. It is an intimate moment as both figures gaze at one another, the viewer observes. The domestic setting reflects Raphael’s intent to portray first and foremost the love between a mother and her child, reified by the central placement of their hands within the composition: Raphael’s primary occupation was their connection.

And a personal favourite

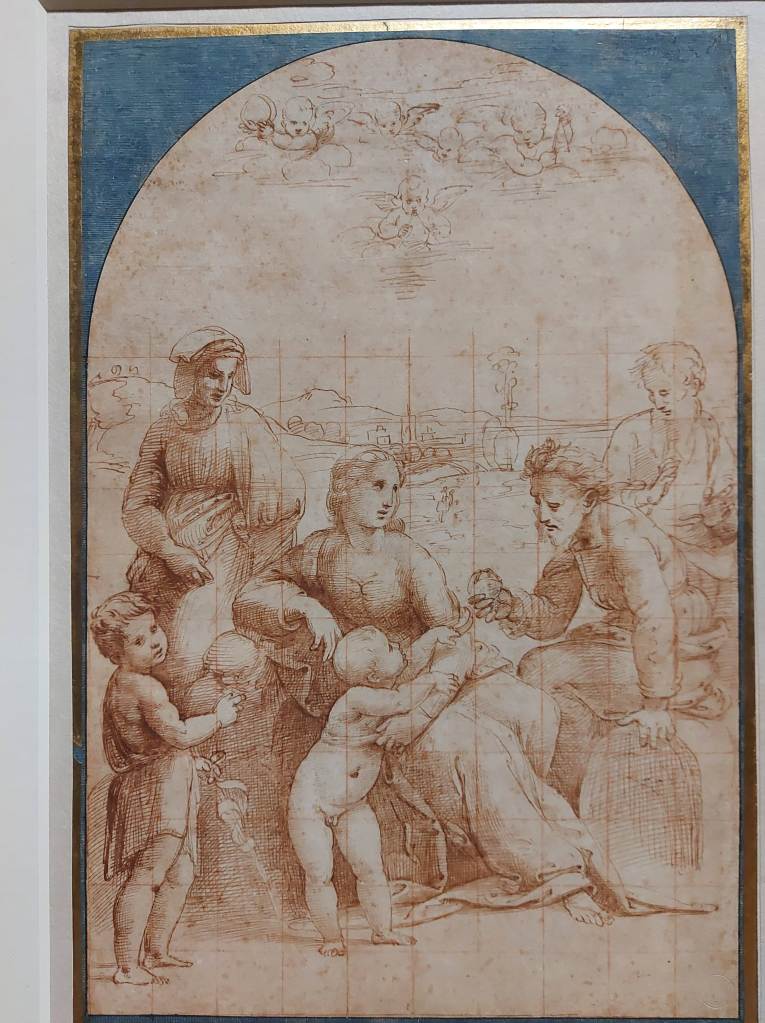

“Raphael was generous towards other artists throughout his career and provided designs for several of them to work from.” At first glance I thought this drawing was incredibly detailed for a preliminary sketch, and it was then I learnt this drawing was sent to a friend and fellow artist of Raphael, Domenico Alfani (about 1480/5-after 1553). Raphael sent this highly finished drawing from Florence to Domenico Alfani in Perugia, near central Italy, who used it to create an altarpiece in 1510, formerly in the church of Santi Simone e Giuda, Perugia. It was before creating the painting that Alfani added the grid, squaring up the drawing to transfer and enlarge the proportions. The drawing is another example of Raphael’s excellence in creating narratives between the characters, as eyes and hands, robes and limbs seem to continue their course of movement, even after the artist has finished his process.

I sincerely hope you can make it to the exhibition- the careful curation, lighting, colours and textures make you feel the pure joy that Art should make one feel, as the artist is reflected in his work. Raphael’s appreciation for the tenacity that is required to develop a talent is inspirational for any creatives and art lovers alike.

Raphael is on at The National Gallery from 9 April – 31 July. Tickets are £24 for adults.

There are a range of events at the Gallery and online to celebrate the exhibition and the artist, for example, Drawing and Mindfulness: Raphael as a draughtsman, Raphael: Universal Artist Weekend Conference, The Linbury Lecture: Patricia Rubin. Details and other events can be viewed here.